From a can of beer on the ground at a music festival in Australia, to one of the few remaining Sikerei in Mentawai, eating Sago in their Uma. A global economy intertwines those who’ve never met, in a hidden cause and effect.

- Plastic and aluminium Single Use Containers (SUCs) have devastating but disproportionate impacts on human health and the environment

- Case study of Australia and Indonesia show that consumption of SUCs in Australia has impacted negatively upon Indonesia

- Indigenous communities are the most disproportionately impacted, as they do not contribute to the consumption that damages the environment, yet their way of life relies on healthy ecosystems

- Shifting towards a circular economy in Australia would greatly reduce these impacts

- IEF works with partners YBPM and Ranu Welum to support impacted Indigenous communities

- IEFs has also partnered with B-Alternative to minimise the damages from SUC consumption, and the consumption itself via circular economy initiatives, while simultaneously fundraising to support Indonesian partners

Donate to IEF via the Container Deposit Scheme

1. Download the CDS app relevant to your area and/or zone.

2. Go to the charities, causes or donations section and search for ‘Indigenous Education Foundation’.

3. Set IEF as your preferred payout.

4. Then, at your local refund station, open your CDS app and hold your barcode up to the station’s scanner.

5. Simply deposit your containers and 100% of all donations will be used to support Indigenous-led cultural and ecological education via IEF.

With global trade, comes global harms and global responsibilities. As this article will show, Indigenous peoples in Indonesia are negatively impacted by the consumption of single use containers (SUCs) in Australia.

IEF works with partners Suku Mentawai, and Ranu Welum to support Indigenous communities in Indonesia and the Asia-Pacific with their Indigenous-led cultural and ecological education-based programs. Through another partnership with B-Alternative, IEF has begun raising funds at events in Australia to support the important work of these partners in Indonesia, as well as reducing some of the consumer behaviour that negatively impacts Indigenous peoples in Indonesia by promoting a shift to a circular economy.

Single Use Containers (SUCs) are very common items in our modern world. Whether it’s some plastic cutlery, an aluminium soda can or a plastic water bottle, we come across them daily. You need to venture far into the wilderness to avoid SUCs being sold or offered to you. Even then, you might find some littering the forest floor of floating down a stream. SUCs pollute the environment, impact upon human health, and contribute to climate emissions. They have serious environmental consequences and contribute to social injustices (Photo 1).

Photo 1 – A young child playing in rubbish surrounding her home in Muara Siberut. Photo by Rob Henry, 2015.

Photo 1 – A young child playing in rubbish surrounding her home in Muara Siberut. Photo by Rob Henry, 2015.

These items have an incredibly limited function. All the energy and materials used in designing, manufacturing, producing and delivering, only to be used momentarily, and then discarded. While their design may be clever in consideration of convenience, in terms of sustainability they’re inherently flawed. This linear model of make, use and discard leads to alarming levels of production and disposal that our planet cannot cope with. For each person, each week, mass equalling more than our body weight is produced (1), leaving anthropogenic mass growing beyond the weight of all the living biomass on earth (1). Huge amounts of this mass are now discarded items, piling up in overflowing landfills or in the environment, polluting our world. We produce so much excess that we are now running out of landfill space in Australia (2).

We produce so much waste that we are now running out of landfill space in Australia.

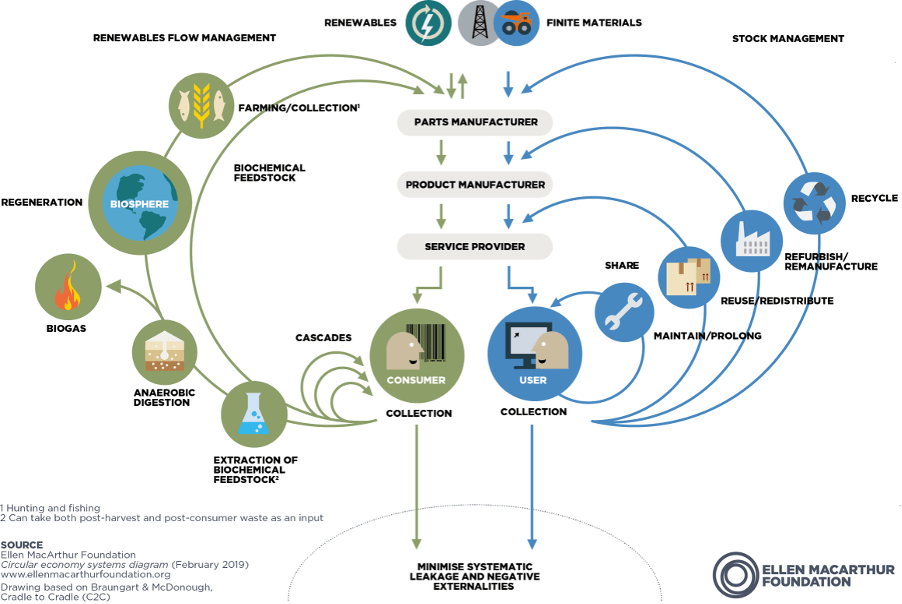

This excess production uses our resources, creates more greenhouse gas emissions and pollutes our environment. Alternate to this broken system, there is the solution of moving to a circular economy (Figure 1). This concept reduces environmental degradation by prioritizing reuse, recycling, refurbishment and reduction (3). Instead of designing items to be immediately trashed after use, they are designed to be long lasting or to be fed back into the system, reducing our reliance on raw materials, reducing emissions and pollution, and reducing waste and landfill use.

Figure 1 – Visualising the circular economy. Source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Circular economy systems diagram (February 2019). Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy-diagram

SUCs are often produced from plastic, a material that is wreaking havoc on our world. We’ve created so much plastic it’s becoming part of the Earth’s fossil record and creating a new marine microbial habitat termed the ‘plastisphere’ (4). As of 2017 we had created 8300 million metric tons of plastic, 6300 million metric tons of which has already become waste (5). 79% of this waste is now either in landfills or the natural environment (5). Plastic pollution is extremely harmful to the environment and to human health. It’s been identified as a major driver in the degradation of ecosystems, it contributes to biodiversity loss, and it worsens climate change (6). Plastics impacts on human health and human rights are also being recognized as they contain hazardous substances that contaminate air, soil, water and our food chains (7). Plastics can be linked to severe environmental contamination of Indigenous Peoples land, violating their rights to a healthy environment, health, water, food, culture and self-determination (7). A staggering 40% of the damaging plastics we produce every year are SUCs (8).

Here in Australia, we are the world’s worst individual contributors. While our waste statistics appear tame when looking at country totals, our small population belies an unsettling fact. A report by the Minderoo Foundation found Australia to have the highest rate of plastic waste per person, in the whole world (9), weighing in at 59kg per person per year. Compare this to neighbouring Indonesia, at 9kg per person, you can see individual contributions are vastly different. Australia also sits above the worlds average for dumping plastics, with an enormous 84% of our consumed plastics going to landfill (10). A large part of this plastics mess, is SUCs. They account for a shocking one million tonnes of Australia’s annual plastic consumption (10).

Australia has the highest rate of plastic waste per person, in the whole world, weighing in at 59kg per person per year.

Despite high-income countries generating more plastic waste per capita, most plastic pollution is emitted from low-to-middle income countries (11). This can be seen in Indonesia, in a list of the worlds most polluted rivers, Indonesia has 4 of the top 20 (12). Some use this fact to diminish the responsibility of high-income countries, like Australia, but many low-to-middle income countries lack the waste management infrastructure that high-income countries can afford (11). Worsening this situation is the global waste trade. This trade increases global disparities as it often involves wealthier countries dumping their waste onto lower-income countries lacking in environmental regulation or waste management infrastructure (Photo 2). This is highly exploitative of the people living in those countries. An example of this trade occurred between Australia and Indonesia.

Photo 2 – A man sorting through imported waste from other countries, including Australia. Source: https://www.no-burn.org

Australia’s waste exports to Indonesia have caused lasting harm to people and the environment.

North Sumengko in East java was transformed from maize and rice fields to a landscape of plastic waste piles (14). Communities in Bangun and Tropodo of East Java were inundated with plastic waste from these imports, and it harmed local people (15). Studies conducted here found the dumping of Australia’s plastic to be linked to high levels of dioxins, PFOS and other banned chemicals in the local food chains (15). Communities in East Java lack the capacity to manage this waste and many resort to burning the plastic accumulating in their villages, which pollutes the air, creating more health impacts for communities in Indonesia (14) (Photo 3).

Photo 3 – Imported plastic waste being used as fuel in a tofu factory, Surabaya, Indonesia. Source: https://www.no-burn.org/discarded-report

Photo 3 – Imported plastic waste being used as fuel in a tofu factory, Surabaya, Indonesia. Source: https://www.no-burn.org/discarded-report

High-income countries – including Australia – need to end exploitative practices like waste exports and pay reparations for past damages.

Plastic is not the only material SUCs are made from. Aluminium has the reputation of being plastics sustainable alternative. Aluminium has its own concerns however, and the impacts of Australia’s aluminium use have also been felt in Indonesia. Australia is a large consumer of aluminium, with Australian’s currently using over 9 billion aluminium cans each year (16). This is equal to 330 cans per person, per year. Aluminium is produced by mining and refining Bauxite ore and Indonesia is the world’s sixth largest producer of Bauxite (17). This large industry has devastating impacts for local communities.

The Bauxite industry does not provide much benefit for local communities, but it is very harmful. It has been linked to heavy metal contamination in soil, air and water, increasing flood risk, increasing flood severity, sediment pollution in rivers and deforestation (18). Contamination, floods and pollution all impact upon the people living on the land. Bauxite mining has destroyed farming land and made fishing more difficult by muddying rivers (18). Links have also been made between the mining industry and health impacts with people developing rashes and boils, attributed to heavy metals polluting the waterways (17). Impacting the environment, health and livelihoods, aluminium can be extremely harmful (Photo 4).

Photo 4 – Bauxite mines in Kalimantan, Indonesia cause widespread deforestation with cascading environmental and social effects. Source: https://dialogue.earth/en/pollution/indonesia-gambles-bauxite/

Photo 4 – Bauxite mines in Kalimantan, Indonesia cause widespread deforestation with cascading environmental and social effects. Source: https://dialogue.earth/en/pollution/indonesia-gambles-bauxite/

Some estimates suggest that Indonesia’s rapidly expanding mining industry has already devastated the traditional ways of life for thousands of Indonesian communities (20). Whenever the environment is degraded, Indigenous people, who live in connection with the land, are threatened as their way of life relies on healthy ecosystems. Between 2001 and 2020, of all the countries who experienced deforestation due to mining, Indonesia had the highest loss (20). The impacts of this can be seen with Indigenous communities in Mentawai and Kalimantan. As the government leased large sections of Indigenous lands to foreign logging companies, many were forcibly moved from their land and their traditional ways, which these communities rely on to survive, were disrupted (21). Pressures to leave such traditions behind have imposed an array of challenges to the people of these communities (21).

There is another way communities like the Mentawai and Dayak peoples are impacted by Australia’s consumption. Our atmosphere is transboundary. Every unit of greenhouse gas we emit, damages the climate for everyone, and disproportionately impacts low-to-middle income nations and Indigenous peoples. Both the production of plastics and aluminium contribute to global warming. Centre for International Environmental Law (CIEL) has warned that to limit global warming to 1.5C, growth in plastic production must be halted (22). Between 3% and 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions have been attributed to plastics and that number is projected to increase (22). Aluminium is also a huge contributor to emissions, ranking as the most carbon intensive of the top three highest emitting materials (23). Aluminium was responsible for about 3% of the world’s direct industrial emissions in 2022, the equivalent of 270 million metric tons (24). The emissions intensity of aluminium production has been decreasing, but the overall emissions have still been increasing due to increasing production (24).

Our atmosphere is transboundary. Every unit of greenhouse gas we emit, damages the climate for everyone, and disproportionately impacts low-to-middle income nations and Indigenous peoples.

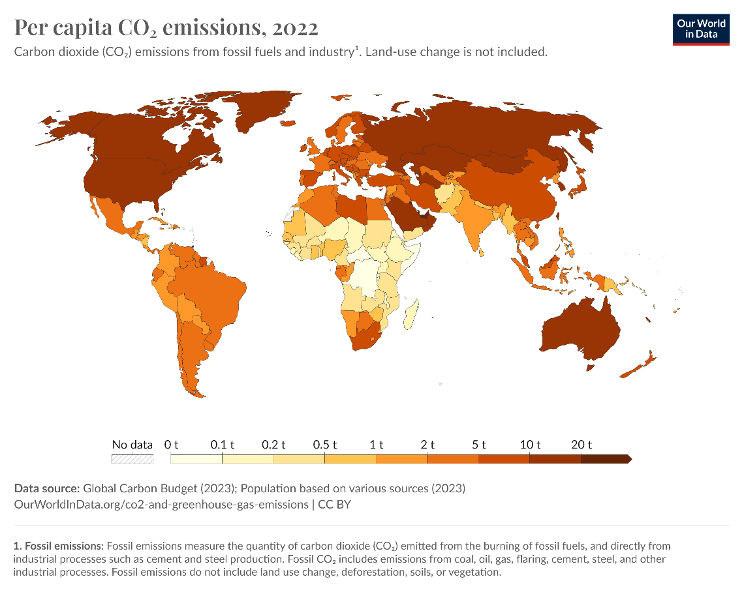

While some would place the aluminium emissions responsibilities upon Indonesia as the bauxite producing country, the responsibility should fall on consuming countries like Australia. The responsibility for a product’s emissions is that of the product consumer, not the producer. This is known as embodied emissions. Some emissions calculations fail to consider embodied emissions and show high-income countries as decarbonizing (25). As production moved offshore for many high-income nations, the emissions from their consumption were moved with them. Embodied emissions calculations rightfully bring these emissions, and responsibility, back to the consumers. High-income nations like Australia are overwhelmingly the largest contributors per capita to the climate crisis (Figure 2). In a study that considered all countries equal access to the atmospheric commons, and calculated total emissions over time, the Global North was found to be responsible for 92% of global carbon emissions while the Global South emitted within their fair shares (26).

Figure 2 – Per capita CO2 emissions. Australia uses considerably over our fair share of the atmospheric commons. However, this graph still doesn’t include embedded emission from trade. Source: https://ourworldindata.org

While low-to-middle income countries will be disproportionately impacted, Indigenous groups around the world are even more disproportionately affected by climate emissions. Indigenous groups contribute the least to climate emissions, yet they are some of the first to suffer its consequences (28). Climate change worsens Indigenous losses of land and resources, political and economic marginalization, discrimination, unemployment and human rights violations (28). Indigenous groups are important environmental protectors (Photo 5). They tend to live harmoniously within their environments, contributing sustainably to the function of ecosystems, often enhancing the resilience of these ecosystems (28).

Photo 5 – Through the Youth Climate Act, Ranu Welum is mobilizing Indigenous youth to fight for the protection and restoration of their ancestral lands — reclaiming both nature and cultural heritage.”

Photo 5 – Through the Youth Climate Act, Ranu Welum is mobilizing Indigenous youth to fight for the protection and restoration of their ancestral lands — reclaiming both nature and cultural heritage.”

Indigenous groups are important environmental protectors. They tend to live harmoniously within their environments, contributing sustainably to the function of ecosystems, often enhancing the resilience of these ecosystems.

In Indonesia, the Simardangiang Indigenous community safeguards its forests using the local wisdom and the traditional practice of ‘Parpatihan’ (30). This management of their customary lands protects it from deforestation and preserves biodiversity (30). As Indonesia is the world’s second most biodiverse country (31), this is of global importance to environmental efforts. As guardians of the environment, Indigenous communities play a central role in protecting earths biodiversity (32). They manage the health of local and regional ecosystems, and these contributions have global implications (33). Indigenous peoples also contribute creative solutions to climate change with their traditional knowledge and unique interpretations (28).

IEFs partners work to support Indigenous communities in Indonesia, on the island of Kalimantan and in the Mentawai islands. One of IEFs partners, Ranu Welum, is working to protect the forests of Kalimantan, preserve Indigenous culture of the Dayak people and fight for Indigenous rights. This Indigenous led foundation has already protected 2,271 hectares of forest and are currently working to save 30 hectares of Talekoi Forest in Central Kalimantan from being sold to mining companies (Photo 6). They’re also working to ensure their ecological knowledge is passed to the next generation (Photo 7). Another partner, Suku Mentawai, works to empower Indigenous youth in the Mentawai islands. They are also Indigenous led, and have created cultural learning hubs to preserve their Indigenous culture. They help Indigenous youth to preserve their culture, fight for Indigenous rights and protect the forests (Photo 8). They aim to improve long-term health and wellbeing by supporting the integration of indigenous knowledge and understanding within the day-to-day education of the local Mentawai community.

Photo 6 – The Talekoi Forest in Central Kalimantan is safeguarded through the efforts of the Ranu Welum Foundation, preserving vital ecosystems and Indigenous heritage.

Photo 6 – The Talekoi Forest in Central Kalimantan is safeguarded through the efforts of the Ranu Welum Foundation, preserving vital ecosystems and Indigenous heritage.

Photo 7 – Young Dayak students learn ancestral ecological wisdom, preserving a legacy of stewardship for generations to come.

Photo 7 – Young Dayak students learn ancestral ecological wisdom, preserving a legacy of stewardship for generations to come.

Photo 8 – Mentawai students are reclaiming their roots through the Suku Mentawai program — safeguarding their language, culture, and traditional lands for generations to come.

IEF has also partnered with B-Alternative to tackle the SUC problem in Australia, whilst offsetting some of the damages SUCs cause to Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia and beyond. B-Alternative has a circular economy focus, working to reduce the consumption of SUCs at events in Australia by sustainably managing waste streams, educating patrons and providing reusable alternatives to SUCs (Photo 9). IEF and B-Alternative are starting a new project together, where SUCs currently circulating at festivals will be collected. These SUCs will then be processed through the Victoria Container Deposit Scheme, ensuring more SUCs are appropriately recycled and raising funds. The funds raised will be given to IEFs Indigenous partners, so they can continue to support their communities with programs that enable access to and strengthen their cultural and ecological education. A knowledge built upon sustainable practice nurturing the natural environment through harmonious relationships conducive to protecting health of the planet and its inhabitants.

Photo 9 – B-Alternative and IEF have been collaborating to reduce the damage of SUCs at public events and festivals, whilst raising funds for IEF partner programs.

Photo 9 – B-Alternative and IEF have been collaborating to reduce the damage of SUCs at public events and festivals, whilst raising funds for IEF partner programs.

To support the work of IEF, please donate here.

You could also support and learn more by watching our feature documentary film As Worlds Divide.

Please share amongst your networks.

Author: Schayla Ray Wakeling

References

- Elhacham E, Ben-Uri L, Grozovski J, Ban-Or YM and Milo R (2020) ‘Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass’, Nature, 588(7838):422-444, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5.

- Taylor L (2020) ‘What is the linear economy and why do we need to go circular?’ Australian Circular Economy Hub, accessed 20 March 2025.

- UNEP (United nations Environment Programme) (n.d.) ‘Circular economy’, UNEP, accessed 20 March 2025.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2024) ‘Our Plant is choking in Plastic’, UNEP, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Geyer R, Jambeck JR and Law KL (2017) ‘Production, use and fate of all plastics every made’, Science Advance, 3(7), DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) (2024) ‘Plastic pollution’, IUCN, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Global Toxics and Human Rights Project (2024) ‘The stages of the plastics cycle and their impacts on human rights’, OHCR (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner), accessed June 29, 2024.

- Parker L (2024) ‘The world’s plastic pollution crisis, explained’, National Geographic, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Charles D, Kimman L and Saran N (2021) The plastic waste makers index: revealing the source of the single-use plastics crisis, Minderoo Foundation, accessed 20 March 2025.

- DAWE (Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment) (2021) ‘National plastics plan summary’,DAWE, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Ritchie H (2021) ‘Where does the plastic in our oceans come from?’ Our World in Data, accessed 20 march 2025.

- Lotulung G (2023) ‘Indonesia is drowning in plastic, but with action comes hope’, Fair Planet, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Walden M, and Renaldi E (2019) ‘Indonesian Environmentalists accuse Australia of ‘smuggling’ plastic waste following China ban’, ABC News, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Gaia (2023) Indonesia, ‘treasure in the trash’, Gaia, accessed June 29, 2024.

- IPEN (International Pollutants Elimination Network) (2019) ‘Plastic Waste Poisons Indonesia’s Food Chain’, IPEN, accessed June 29, 2024.

- Australian Aluminium Council (2023) Aluminium cans market assessment Australia, Australian Aluminium Council, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Mighty Earth (2024) ‘The impact of the bauxite boom on people and planet, Mighty Earth, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Pahlevi A, Sentosa VF and Morse I (2021) ‘Indonesia gambles on bauxite’, Dialogue earth, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Fatmawati (2018) Social Injustice from the presence of the bauxite mining companies, ‘International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications’, 6(6):317-322, accessed 30 March 2025.

- Wahil Y and Milko V (19 December 2024) ‘Global demand spurring Indonesia’s mining boom comes at a cost for many communities’, The Associated Press, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Henry R (director and producer) (2017) ‘As worlds divide’ [documentary], Indigenous Education Foundation, Melbourne.

- Gonzalez DD, Radvany R and Azoulay D (2023) ‘Reducing plastic production to achieve climate goals’, CIEL (Centre for International Environmental Law), accessed June 29, 2024.

- de Berker A (2022) ‘Understand your aluminium emissions’, High-carbon commodities blog series, Carbon Chain, accessed 20 March 2025.

- IEA (International Energy Agency) (n.d.) Energy system: Industry: Aluminium, International Energy Agency, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Wood R, Grubb M, Anger-Kraavi A, Pollitt H, Rizzo B Alexandri E, Stradler K, Moran D, Hertwich E and Tukker A (2019) ‘Beyond peak emission transfers: historical impacts of globalization and future impacts of climate policies on international emission transfer’, Taylor & Francis, 20(1):14-27, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1619507

- Hickel J (2020) ‘Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary’, The Lancet, 4(9):399-404, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30196-0

- Shan Y (2023) ‘Discussion on how climate change is disproportionately affecting the Global South’. International journal of Frontiers in Sociology, 5(12):10-15, DOI: 10.25236/IJFS.2023.051202

- DESA (Department of Economic and Social Affairs) (n.d.) Climate Change, DESA, United Nations, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Amnesty International (2024) Indigenous Peoples rights, Amnesty International, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Simangunsong T (2024) ‘How Indonesia’s Indigenous tribes protect their lands’, Fair Planet, accessed 20 March 2025.

- Indrajaya Y, Yuwati TW, Lestari S, Winarno B, Narendra BH, Nugroho HYSH, Rachmanadi D, Pratiwi, Turjaman M, Adi RN, Savitri E, Putra PB, Santosa PB, Nugroho NP, Cahyono SA, Wahyuningtyas RS, Prayudyaningsih R, Halwany W, Siarudin M, Widiyanto A, Utomo MMB, Sumardi, Winara A, Wahyuni T and Mendham D (2022) ‘Tropical forest landscape restoration in Indonesia: a review’, MDPI, 11(3):328, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ land11030328

- Garnett S, Fernández-Llamazares Á (2024) ‘For decades, we’ve been told 80% of the world’s biodiversity is found on Indigenous land – but it’s wrong’, The Conversation, accessed 09 May 2025.

- Brondízio E, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Bates P, Carino J, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Ferrari M, Galvin K, Reyes-García V, McElwee P, Molnár Z, Samakov A and Shrestha U (2021) ‘Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: Indigenous and locally knowledge, values and practices for nature’, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46:481-509, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-012127

0 Comments