Language is a shared experience. Imagine a student who returns home from school and lacks the ability to speak with their grandparents, close relatives, or even their parents. Indigenous Mentawai students face that reality every day.

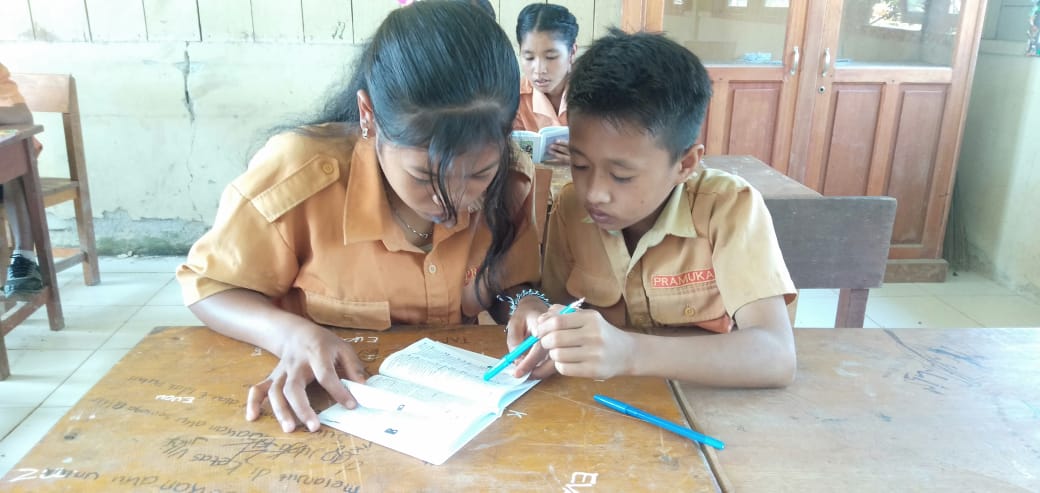

Indigenous Mentawai school and learning hub students communicate using the Mentawai language dictionary, published by @sukumentawai in 2019

Mentawai students learn to speak Bahasa Indonesian because for two generations their indigenous language has been overlooked by formalised education systems. Too often, students are unable to understand the language of their community or find the expression to describe their mood, desires and pain. They are unable to share their experiences at school or with friends, to their parents or other members of the extended family. Determined to ensure their language is not forgotten, Mentawai community leaders and families decided that the educational and language gap needed to be addressed. Their indigenous cultural learning hubs were established as a way to teach young Mentawai students their ancestral language and culture that has sustained their community for millennia.

Because many of the children now learn through books and writing, the first Mentawai (Rereiket)-Indonesian dictionary was produced. Now, their aim is to develop an English translation of this dictionary. But, translating Mentawai is a significant challenge, including the difficulty of translating many of Mentawai’s unique words, concepts and underlying cultural meaning into a foreign language. For example, the Mentawai word sitamaniu refers to a person who doesn’t have a sister; a concept that does not exist in Indonesian, nor English.

Interestingly, when the Mentawai phrase pulu mongi is literally translated, it implies a person is referring to a time ten days in advance. Whereby, this actually means very early the following morning. Another example refers to the terms jiji and kolik, which are the interim names given to all girls (jiji) and boys (kolik) from birth through until they receive their names, which can be two or more years after they are born. If this is their first-born child, during this time the parents will also be termed Bai Jiji or Bai Kolik (mother of Jiji/Kolik) and Aman Jiji or Aman Kolik (father of Jiji/Kolik). This concept does not exist in the Indonesian or English languages, making this – and many other Mentawai relationship ties and ancestral connections – difficult to translate in any other language.

The United Nations Decade of Indigenous Languages is the world’s peak institution’s effort to raise awareness of the role languages play in First Nation communities and their ties to education, history, tradition, and memory. The underlying purpose of this dedicated decade is to enhance the respect, recognition and preservation of indigenous languages and to prevent further erosion of linguistic diversity that defines us as humans inhabiting a fragile world. The Mentawai community believe that by empowering their children to effectively communicate in English they will be better equipped to represent themselves with boldness and to advocate the continued preservation of their forest (a declared United Nations Man and Biosphere reserve) that generations of Mentawai have kept in pristine condition.

Mentawai school students utilising the @sukumentawai Foundation’s dictionary publication to learn their ancestral language

To support the Mentawai’s endeavours to publish a Mentawai (Rereiket)-English language dictionary, building capacity and communication skill within their own community and with the wider world that visit this remote part of Indonesia, please visit our fundraiser page here or contact our volunteer team at IEF.

Masura’ bagatta, thank you.

0 Comments